TO PAY THE PIPER

BY JAMES BLISH

Clearly, re-educating Man's brain wouldn't

fit him for survival on the plague-ridden

surface. Re-educating his body was the answer;

but the process was so very long....

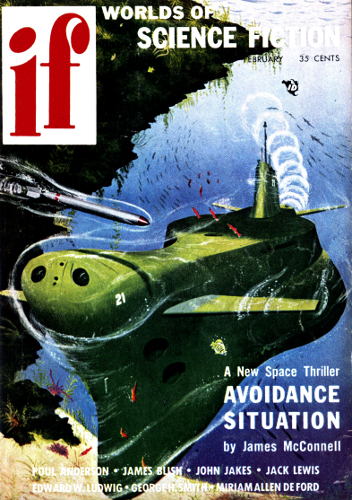

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, February 1956.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The man in the white jacket stopped at the door marked "Re-EducationProject—Col. H. H. Mudgett, Commanding Officer" and waited while thescanner looked him over. He had been through that door a thousandtimes, but the scanner made as elaborate a job of it as if it had neverseen him before.

It always did, for there was always in fact a chance that it hadnever seen him before, whatever the fallible human beings to whom itreported might think. It went over him from grey, crew-cut poll toreagent-proof shoes, checking his small wiry body and lean profileagainst its stored silhouettes, tasting and smelling him as dubiouslyas if he were an orange held in storage two days too long.

"Name?" it said at last.

"Carson, Samuel, 32-454-0698."

"Business?"

"Medical director, Re-Ed One."

While Carson waited, a distant, heavy concussion came rolling downupon him through the mile of solid granite above his head. At the samemoment, the letters on the door—and everything else inside his coneof vision—blurred distressingly, and a stab of pure pain went lancingthrough his head. It was the supersonic component of the explosion, andit was harmless—except that it always both hurt and scared him.

The light on the door-scanner, which had been glowing yellow up tonow, flicked back to red again and the machine began the whole routineall over; the sound-bomb had reset it. Carson patiently endured itsinspection, gave his name, serial number and mission once more, andthis time got the green. He went in, unfolding as he walked the flimsysquare of cheap paper he had been carrying all along.

Mudgett looked up from his desk and said at once: "What now?"

The physician tossed the square of paper down under Mudgett's eyes."Summary of the press reaction to Hamelin's speech last night," hesaid. "The total effect is going against us, Colonel. Unless we canchange Hamelin's mind, this outcry to re-educate civilians ahead ofsoldiers is going to lose the war for us. The urge to live on thesurface again has been mounting for ten years; now it's got a target tofocus on. Us."

Mudgett chewed on a pencil while he read the summary; a blocky, bulkyman, as short as Carson and with hair as grey and close-cropped. Ayear ago, Carson would have told him that nobody in Re-Ed could affordto put stray objects in his mouth even once, let alone as a habit;now Carson just waited. There wasn't a man—or a woman or a child—ofAmerica's surviving thirty-five million "sane" people who didn't havesome such tic. Not now, not after twenty-five years of underground life.

"He knows it's impossible, doesn't he?" Mudgett demanded abruptly.

"Of course he doesn't," Carson said impatiently. "He doesn't know anymore about the real nature of the project than the people do. He thinksthe 'educating' we do is in some sort of survival technique—That'swhat the papers think, too, as you can plainly see by the way theyloaded that editorial."

"Um. If we'd taken direct control of the papers in the first place—"

Carson said nothing. Military control of every facet of civilian lifewas a fa