Transcriber's Note.

Variable spelling and hyphenation have been retained.Minor punctuation inconsistencies have been silently repaired.The author's corrections, additions and comments have been applied in the text and are indicated like this.Changes made by the transcriber are indicated like this and alist can be found at the end of the book.The original text is printed in a two-column layout.

THE

LIFE

OF

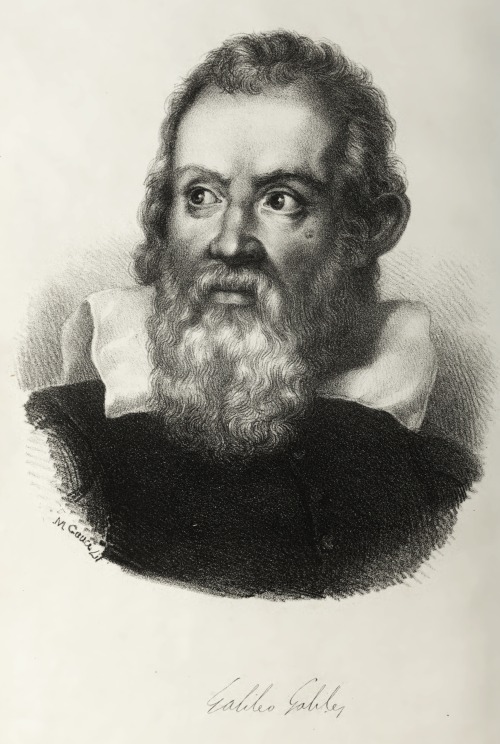

GALILEO GALILEI,

WITH

ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE ADVANCEMENT

OF

EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY.

MDCCCXXX.

LONDON.

LIFE OF GALILEO:

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE ADVANCEMENTOF EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY.

Chapter I.

Introduction.

The knowledge which we at presentpossess of the phenomena of nature andof their connection has not by anymeans been regularly progressive, as wemight have expected, from the timewhen they first drew the attention ofmankind. Without entering into thequestion touching the scientific acquirementsof eastern nations at a remoteperiod, it is certain that some amongthe early Greeks were in possession ofseveral truths, however acquired, connectedwith the economy of the universe,which were afterwards suffered to fallinto neglect and oblivion. But the philosophersof the old school appear ingeneral to have confined themselves atthe best to observations; very few tracesremain of their having instituted experiments,properly so called. This puttingof nature to the torture, as Bacon callsit, has occasioned the principal part ofmodern philosophical discoveries. Theexperimentalist may so order his examinationof nature as to vary at pleasurethe circumstances in which it is made,often to discard accidents which complicatethe general appearances, andat once to bring any theory which hemay form to a decisive test. The provinceof the mere observer is necessarilylimited: the power of selection amongthe phenomena to be presented is ingreat measure denied to him, and hemay consider himself fortunate if theyare such as to lead him readily to aknowledge of the laws which they follow.

Perhaps to this imperfection of methodit may be attributed that naturalphilosophy continued to be stationary,or even to decline, during a long seriesof ages, until little more than two centuriesago. Within this comparativelyshort period it has rapidly reached adegree of perfection so different from itsformer degraded state, that we canhardly institute any comparison betweenthe two. Before that epoch, a few insulatedfacts, such as might first happento be noticed, often inaccurately observedand always too hastily generalized,were found sufficient to excite thenaturalist's lively imagination; and havingonce pleased his fancy with the supposedfitness of his artificial scheme,his perverted ingenuity was thenceforwardemployed in forcing the observedphenomena into an imaginary agreementwith