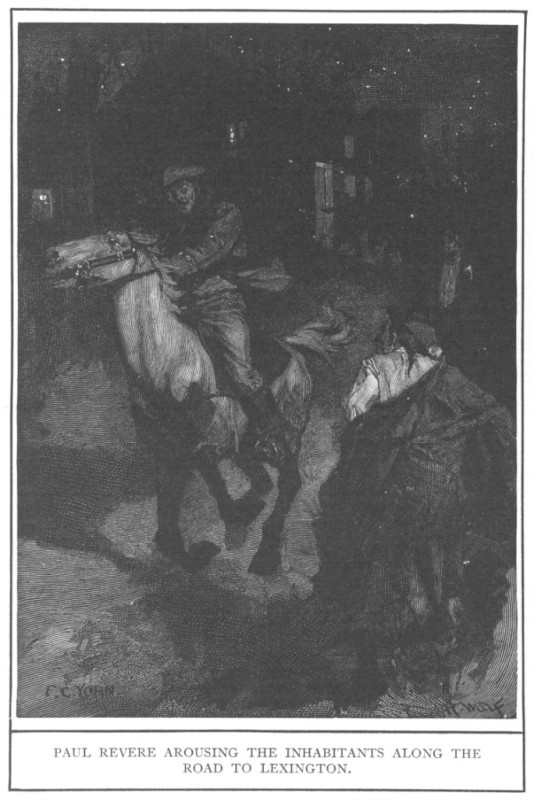

PAUL REVERE AROUSING THE INHABITANTS ALONG THEROAD TO LEXINGTON.

PAUL REVERE AROUSING THE INHABITANTS ALONG THEROAD TO LEXINGTON.AMERICAN LEADERS

AND HEROES

A PRELIMINARY TEXT-BOOK IN

UNITED STATES HISTORY

BY

WILBUR F. GORDY

PRINCIPAL OF THE NORTH SCHOOL, HARTFORD, CONN.; AUTHOR OF

"A HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES FOR SCHOOLS"; AND

CO-AUTHOR OF "A PATHFINDER IN AMERICAN HISTORY"

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1907

COPYRIGHT, 1901, BY

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

[Pg v]

PREFACE

In teaching history to boys and girls from ten totwelve years old simple material should be used.Children of that age like action. They crave thedramatic, the picturesque, the concrete, the personal.When they read about Daniel Boone or AbrahamLincoln they do far more than admire their hero.By a mysterious, sympathetic process they so identifythemselves with him as to feel that what they see inhim is possible for them. Herein is suggested theethical value of history. But such ethical stimulus,be it noted, can come only in so far as actions aretranslated into the thoughts and feelings embodied inthe actions.

In this process of passing from deeds to the heartsand heads of the doers the image-forming power playsa leading part. Therefore a special effort should bemade to train the sensuous imagination by furnishingpicturesque and dramatic incidents, and then so skilfullypresenting them that the children may get livingpictures. This I have endeavored to do in the preparationof this historical reader, by making prominentthe personal traits of the heroes and leaders, as they[Pg vi]are seen, in boyhood and manhood alike, in the environmentof their every-day home and social life.

With the purpose of quickening the imagination,questions "To the Pupil" are introduced at intervalsthroughout the book, and on almost every page additionalquestions of the same kind might be suppliedto advantage. "What picture do you get in thatparagraph?" may well be asked over and over again,as children read the book. If they get clear and definitepictures, they will be likely to see the past asa living present, and thus will experience anew thethoughts and feelings of those who now live only intheir words and deeds. The steps in this vital processare imagination, sympathy, and assimilation.

To the same end the excellent maps and illustrationscontribute a prominent and valuable feature ofthe book. If, in the elementary stages of historicalreading, the image-forming power is developed, whenthe later work in the study of organized history isreached the imagination can hold the outward eventbefore the mind for the judgment to determine itsinner significance. For historical interpretation isbased upon the inner life quite as much as upon theoutward expression of that life in action.

Attention is called to the fact that while the biographicalelement predominates, around the heroesand leaders are clustered typical and significant eventsin such a way as to give the basal facts of Americanhistory. It is hoped, therefore