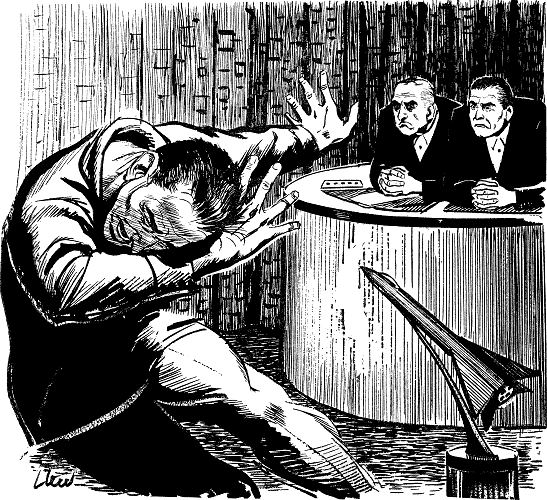

Their combined thought-force hit him like a thunderbolt.

Their combined thought-force hit him like a thunderbolt.THE

PENAL

CLUSTER

By IVAR JORGENSEN

Tomorrow's technocracy willproduce more and more thingsfor better living. It willproduce other things, also;among them, criminals toodespicable to live on thisearth. Too abominable tobreathe our free air.

The clipped British voicesaid, in David Houston'sear, I'm quite sure he's one.He's cashing a check for athousand pounds. Keep himunder surveillance.

Houston didn't look up immediately.He simply stoodthere in the lobby of the bigLondon bank, filling out a depositslip at one of the long,high desks. When he had finished,he picked up the slipand headed towards theteller's cage.

Ahead of him, standing atthe window, was a tall, impeccablydressed, aristocratic-lookingman with grayinghair.

"The man in the tweeds?"Houston whispered. His voicewas so low that it was inaudiblea foot away, and his lipsscarcely moved. But the sensitivemicrophone in his collarpicked up the voice andrelayed it to the man behindthe teller's wicket.

That's him, said the tinyspeaker hidden in Houston'sear. The fine-looking chap inthe tweeds and bowler.

"Got him," whisperedHouston.

He didn't go anywherenear the man in the bowlerand tweeds; instead, he wentto a window several feetaway.

"Deposit," he said, handingthe slip to the man on theother side of the partition.While the teller went throughthe motions of putting thedeposit through the robot accountingmachine, DavidHouston kept his ears open.

"How did you want thethousand, sir?" asked theteller in the next wicket.

"Ten pound notes, if youplease," said the graying man."I think a hundred notes willgo into my brief case easilyenough." He chuckled, asthough he'd made a clever witticism.

"Yes, sir," said the clerk,smiling.

Houston whispered into hismicrophone again. "Who isthe guy?"

On the other side of thepartition, George Meredith, asmall, unimposing-lookingman, sat at a desk marked:MR. MEREDITH—ACCOUNTINGDEPT. He lookedas though he were payingno attention whatever to anythinggoing on at the variouswindows, but he, too, had amicrophone at his throat anda hidden pickup in his ear.

At Houston's question, hewhispered: "That's Sir LewisHuntley. The check's good, ofcourse. Poor fellow."

"Yeah," whispered Houston,"if he is what we thinkhe is."

"I'm fairly certain," Meredithreplied. "Sir Lewis isn'tthe type of fellow to drawthat much in cash. At thepresent rate of exchange,that's worth three thousandseven hundred and fifty dollarsAmerican. Sir Lewismight carry a hundredpounds as pocket-money, butnever a thousand."

Houston and Meredith werea good thirty feet from eachother, and neither looked atthe other. Unless a bystanderhad equipment to tune in onthe special scrambled wavelengththey were using, thatbystander would never knowthey were holding a conversation.

"... nine-fifty, nine-sixty,nine-seventy, nine-eighty,nine-ninety, a thousandpounds," said the clerk whowas taking care of Sir Lewis'scheck. "Would you count thatto make sure, sir?"

"Certainly. Ten, twenty,thirty, ..."

While the baronet wasdouble-checking the amount,David Houston glanced athim. Sir Lewis looked perfectlycalm and unhurried, asthough he were doing somethingperfectly legal—which,in a way, he was. And, in anotherway, he most definitelywas not, if George Mer