William Le Queux

"Stolen Souls"

Chapter One.

The Soul of Princess Tchikhatzoff.

Wrapped in furs until only my nose and eyes were visible, I was walking along the Nevski Prospekt in St. Petersburg one winter’s evening, and almost involuntarily turned into the Dominique, that fashionable restaurant which, garish in its blaze of electricity, is situated in the most frequented part of the long, broad thoroughfare. It was the dining-hour, and the place, heated by high, grotesquely-ornamented stoves, was filled with officers, ladies, and cigarette smoke, while the savoury smell of national dishes mingled judiciously with those of foreign lands.

At the table next the one at which I seated myself were two persons, a man and a woman.

The former, who was about fifty, had a military bearing, a pair of keen black eyes, closely-cropped iron-grey hair, and a well-trimmed bushy beard. The woman was young, fair haired, and pretty. Her eyes were clear and blue, her face oval and flawless in its beauty, and she was attired in a style that showed her to be a patrician, wearing over her low-cut evening dress a velvet shuba, lined with Siberian fox; her soft velvet cap was edged with costly otter, and the bashlyk she had removed from her head was of Orenberg goat-wool. On her slim white fingers some fine diamonds flashed, and in the bodice of her dress was a splendid ornament of the same glittering gems, in the shape of a large double heart.

As our eyes met, there appeared something about her gaze that struck me as strange. Her delicately-moulded face was utterly devoid of animation; her eyes had a stony stare—that fixed, unwavering glance that one sees in the glazed eyes of the dead.

Having poured out a glass of the Brauneberger I had ordered, and taken a slight draught, I caught sight of a man I knew who was just leaving, and, jumping up, rushed after him. We remained chatting a few moments in the vestibule, and on returning, I sat down to my soup.

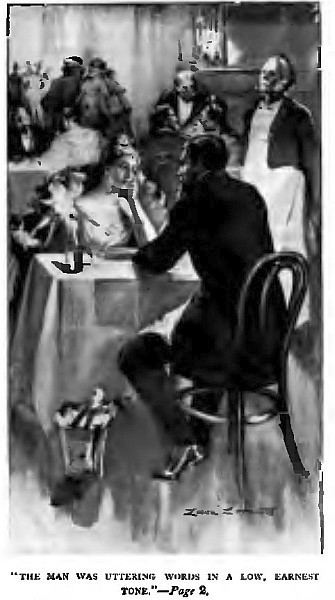

My neighbours were an incongruous pair. The man, who spoke the dialect of the South, was uttering words in a low, earnest tone with a curious, intense look in his eyes, and an expression on his dark, sinister features that filled me with surprise and repulsion. Notwithstanding his excited manner, his fair vis-à-vis remained perfectly calm, gazing at him wonderingly, and answering his questions wearily, in abrupt monosyllables.

Once she turned to me with what I thought was a glance of mute appeal. At last they finished their dessert, and when the man had paid the bill, he rose, exclaiming—

“Come, Agàfia, we must be moving!”

“You—you must go alone,” she said quickly, passing her hand wearily across her brow. “I have that strange sensation again, as if my brain is benumbed. My forehead seems on fire, and I can think of nothing except—except the enormity of my terrible crime.”

And she shuddered.

“Fool! some one will overhear you,” he whispered, with an imprecation. “You are only faint. The drive will revive you.”

As she rose mechanically, he fastened her shuba, then, taking her roughly by the arm, led her out.

Finishing my meal leisurely, I afterwards sat for a long time over my tea and cigar, until I gradually became aware that my mind was wandering strangely, and a curious, apprehensive feeling