This story was published in Analog, February 1963. Extensiveresearch did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on thispublication was renewed.

115

With No Strings Attached

A man will always be willing to buy something he wants, and believesin, even if it is impossible, rather than something he believes isimpossible.

So ... sell him what he thinks he wants!

David Gordon

Illustrated by Schelling

116

The United States Submarine Ambitious Brill slid smoothly intoher berth in the Brooklyn Navy Yard after far too many weeks at sea, asfar as her crew were concerned. After all the necessary preliminarieshad been waded through, the majority of that happy crew went ashore toenjoy a well-earned and long-anticipated leave in the depths of thebrick-and-glass canyons of Gomorrah-on-the-Hudson.

The trip had been uneventful, in so far as nothing really dangerousor exciting had happened. Nothing, indeed, that could even be calledout-of-the-way—except that there was more brass aboard than usual,and that the entire trip had been made underwater with the exception ofone surfacing for a careful position check, in order to make sure thatthe ship’s instruments gave the same position as the stars gave. Theyhad. All was well.

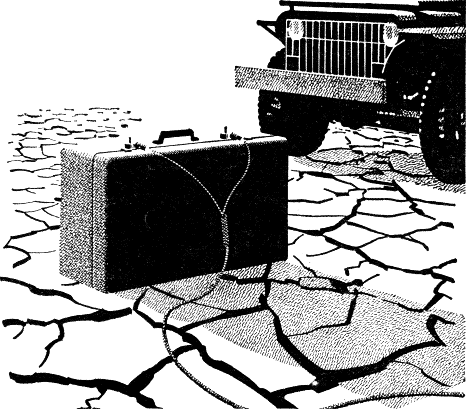

That is not to say that the crew of the Ambitious Brill wereentirely satisfied in their own minds about certain questions that hadbeen puzzling them. They weren’t. But they knew better than to askquestions, even among themselves. And they said nothing whatever whenthey got ashore. But even the novices among submarine crews know thatwhile the nuclear-powered subs like George Washington, PatrickHenry, or Benjamin Franklin are perfectly capable ofcircumnavigating the globe without coming up for air, such performancesare decidedly rare in a presumably Diesel-electric vessel such as theU.S.S. Ambitious Brill. And those few members of the crew who hadseen what went on in the battery room were the most secretive and themost puzzled of all. They, and they alone, knew that some of the cellsof the big battery that drove the ship’s electric motors had beenremoved to make room for a big, steel-clad box hardly bigger than a footlocker, and that the rest of the battery hadn’t been used at all.

With no one aboard but the duty watch, and no one in the battery roomat all, Captain Dean Lacey felt no compunction whatever in saying, as hegazed at the steel-clad, sealed box: “What a battery!”

The vessel’s captain, Lieutenant Commander Newton Wayne, looked upfrom the box into the Pentagon representative’s face. “Yes, sir, it is.”His voice sounded as though his brain were trying to catch up with itand hadn’t quite succeeded. “This certainly puts us well ahead of theRussians.”

Captain Lacey returned the look. “How right you are, commander. Thismeans we can convert every ship in the Navy in a tenth the time we hadfigured.”

Then they both looked at the third man, a civilian.

He nodded complacently. “And at a tenth the cost, gentlemen,” he saidmildly. “North American Carbide & Metals can produce these unitscheaply, and at a rate that will enable us to convert every ship in theNavy within the year.”

117

Captain Lacey shot a glance at Lieutenant Commander Wayne. “All thisis strictly Top Secret you understand.”

“Yes, sir; I understand,” said Wayne.

“Very well.” He looked ba