Transcriber's Note:

This etext was produced from Analog, July 1961.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.

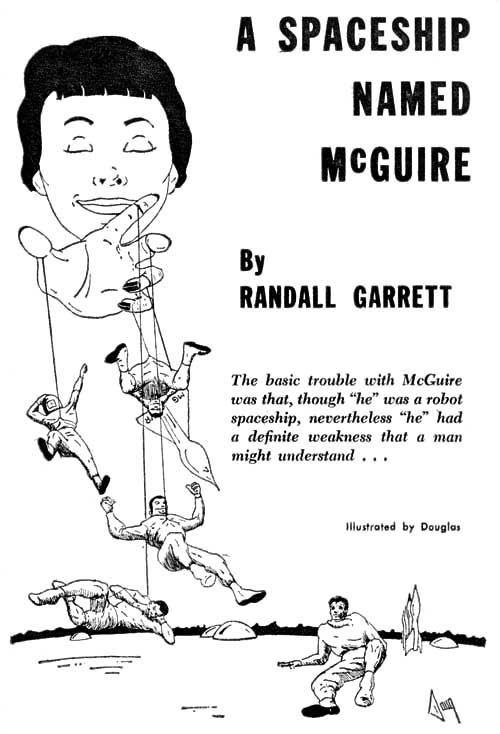

A SPACESHIP

NAMED

McGUIRE

By

RANDALL GARRETT

The basic trouble with McGuire was that, though "he" was arobot spaceship, nevertheless "he" had a definite weaknessthat a man might understand....

Illustrated by Douglas

o. Nobody ever deliberately named a spaceship that. The staid andstolid minds that run the companies which design and build spaceshipsrarely let their minds run to fancy. The only example I can think ofis the unsung hero of the last century who had puckish imaginationenough to name the first atomic-powered submarine Nautilus. Suchminds are rare. Most minds equate dignity with dullness.

This ship happened to have a magnetogravitic drive, whichautomatically put it into the MG class. It also happened to be thefirst successful model to be equipped with a Yale robotic brain, so itwas given the designation MG-YR-7—the first six had had more bugs inthem than a Leopoldville tenement.

So somebody at Yale—another unsung hero—named the ship McGuire; itwasn't official, but it stuck.

The next step was to get someone to test-hop McGuire. They needed justthe right man—quick-minded, tough, imaginative, and a whole slew ofcomplementary adjectives. They wanted a perfect superman to test pilottheir baby, even if they knew they'd eventually have to take secondbest.

It took the Yale Space Foundation a long time to pick the right man.

No, I'm not the guy who tested the McGuire.

I'm the guy who stole it.

Shalimar Ravenhurst is not the kind of bloke that very many people canbring themselves to like, and, in this respect, I'm like a great manypeople, if not more so. In the first place, a man has no right to goaround toting a name like "Shalimar"; it makes names like "Beverly"and "Leslie" and "Evelyn" sound almost hairy chested. You want a dozenother reasons, you'll get them.

Shalimar Ravenhurst owned a little planetoid out in the Belt, a hunkof nickel-iron about the size of a smallish mountain with a gee-pullmeasurable in fractions of a centimeter per second squared. If you'resusceptible to spacesickness, that kind of gravity is about as muchhelp as aspirin would have been to Marie Antoinette. You get thefeeling of a floor beneath you, but there's a distinct impression thatit won't be there for long. It keeps trying to drop out from underyou.

I dropped my flitterboat on the landing field and looked aroundwithout any hope of seeing anything. I didn't. The field was about thesize of a football field, a bright, shiny expanse of rough-polishedmetal, carved and smoothed flat from the nickel-iron of the planetoiditself. It not only served as a landing field, but as a reflectorbeacon, a mirror that flashed out the sun's reflection as theplanetoid turned slowly on its axis. I'd homed in on that beacon, andnow I was sitting on it.

There wasn't a soul in sight. Off to one end of the rectangular fieldwas a single dome, a hemisphere about twenty feet in diameter and halfas high. Nothing else.

I sighed and flipped on the magnetic