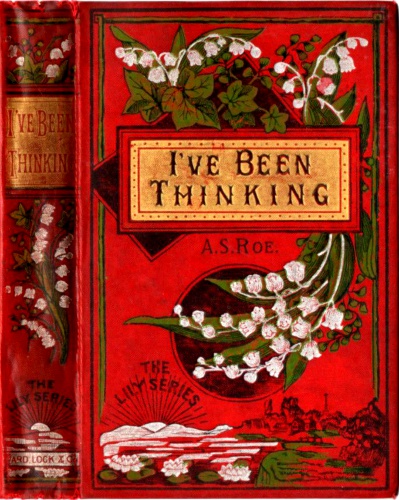

I'VE BEEN THINKING;

OR,

THE SECRET OF SUCCESS.

BY A. S. ROE,

AUTHOR OF "LOOKING ROUND."

WARD, LOCK AND CO.

LONDON, NEW YORK, AND MELBOURNE

I'VE BEEN THINKING.

CHAPTER I.

'Where is the use, Jim, of our working and working to raise so manyvegetables? we never can use them all. Mother said last year there wasno necessity for raising more than we could eat, and now this potatopatch is larger than ever.' And as he said this, the little speakerthrew himself upon the soft ground, struck his hoe into the soil, andlooked up at his brother to see how he would take it.

Jim, as he was called, rested a moment on his hoe, eyed his brotherclosely, and then, with something of a smile, replied:

'Come, Ned, don't give up to lazy feelings; the things will do somebodygood; and you know my father always told us, that it was better to be atwork, even if we got no pay for it: and besides, I have been thinking ofa plan by which we may do something with what we raise, if we have morethan we can use.'

'What plan, Jim?' and Ned raised himself from his prostrate position,and sitting with both hands resting on the ground, looked veryinquiringly at his brother.

'Why, suppose we should try to sell some of the things we raise?'

'Try to sell, Jim? ha, ha, ha!' and the little fellow threw himselfupon the ground, and indulged in a hearty fit of laughter. Jim laughed alittle himself, resuming his work, and hauling the dirt up faster aroundthe potatoes he was hilling.

'Come, Ned, you had better go to work; the sun will soon be down, and weshall not get our task done.'

'Well, tell me then where you are going to sell the things; that'sall.'

'I shall say no more about it now, at any rate; you will only laugh atit. So come, take up your row.'

Ned, perceiving that Jim was working upon both rows, was ashamed towaste any more time, and inspirited by his brother's kindness, sprang tohis feet, and the two boys worked away with alacrity.

The sun had gone down, the cow had been milked and the pigs fed, thehens had all gone to roost, and the two brothers had sauntered towardsthe river which ran before their dwelling, and taken a seat together ona rock under the branches of a huge oak, of which there were severalaround the premises. Before them lay, first; a gentle slope of shortgreensward, part of what was known as the town commons, where everybody's cow, or pig, or goose, could roam unmolested; beyond this lay asmooth sandy shore, washed by a river, whose waters had not far to gobefore they mingled with the ocean, or with a large arm of the ocean;along the shore, as far as the eye could reach, was the same, or nearlythe same, strip of green commons, dotted here and there with small rudedwellings, the abodes of a few fishermen, who existed on the products ofthe river that rolled before them; a few small boats lay drawn up on theshore, and occasionally a row of stakes running out into the water, toldwhere the fishermen had planted their nets. The only house in sight thathad any appearance of comfort was the one these brothers called theirhome—a plain one-story building, with a little wing to it; a paling ranin front and around three sides, enclosing the patch of ground used astheir garden; a few fine old trees threw their shadows over and aroundthe premises, adding much to the domestic aspect of the