Transcribed from the 1845 Thomas Nelson “Works of thePuritan Divines (Bunyan)” edition , email

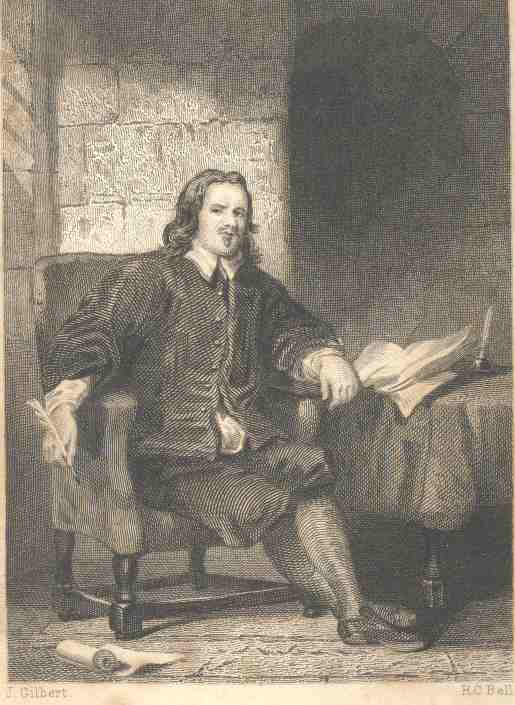

LIFE OF BUNYAN

BY REV. JAMES HAMILTON

SCOTCHCHURCH, REGENT SQUARE, LONDON.

After the pleasant sketches of pensso graceful as Southey’s and Montgomery’s; after theelaborate biography of Mr Philip, whose researches have left fewdesiderata for any subsequent devotee; indeed, afterBunyan’s own graphic and characteristic narrative, the taskon which we are now entering is one which, as we would havecourted it the less, so we feel that we have peculiar facilitiesfor performing it. Our main object is to give a simple andcoherent account of a most unusual man—and then we shouldlike to turn to some instructive purpose the peculiarities of hissingular history, and no less singular works.

John Bunyan was born at Elstow, near Bedford, in 1628. His father was a brazier or tinker, and brought up his son as acraftsman of like occupation. There is no evidence for thegipsy origin of the house of Bunyan; and though extremely poor,John’s father gave his son such an education as poor mencould then obtain for their children. He was sent to schooland taught to read and write.

There has been some needless controversy regardingBunyan’s early days. Some have too readily taken forgranted that he was in all respects a reprobate; andothers—the chief of whom is Dr Southey—have labouredto shew that there was little in the lad which any would censure,save the righteous overmuch. The truth is, that consideringhis rank of life, his conduct was not flagitious; for he neverwas a drunkard, a libertine, or a lover of sanguinary sports: andthe profanity and sabbath-breaking and heart-atheism whichafterwards preyed on his awakened conscience, are unhappily toofrequent to make their perpetrator conspicuous. The thingwhich gave Bunyan any notoriety in the days of his ungodliness,and which made him afterwards appear to himself such a monster ofiniquity, was the energy which he put into all his doings. He had a zeal for idle play, and an enthusiasm in mischief, whichwere the perverse manifestations of a forceful character, andwhich may have well entitled him to Southey’sepithet—“a blackguard.” The reader neednot go far to see young Bunyan. Perhaps there is near yourdwelling an Elstow—a quiet hamlet of some fifty housessprinkled about in the picturesque confusion, and with the easyamplitude of space, which gives an old English village its lookof leisure and longevity. And it is now verging to theclose of the summer’s day. The daws are taking shortexcursions from the steeple, and tamer fowls have gone home fromthe darkening and dewy green. But old Bunyan’s donkeyis still browzing there, and yonder is old Bunyan’sself—the brawny tramper dispread on the settle, retailingto the more clownish residents tap-room wit and roadsidenews. However, it is young Bunyan you wish to see. Yonder he is, the noisiest of the party, playingpitch-and-toss—that one with the shaggy eyebrows, whoseentire soul is ascending in the twirling penny—grim enoughto be the blacksmith’s apprentice, but his singed garmentshanging round him with a lank and idle freedom which scornsindentures; his energetic movements and authoritativevociferations at once bespeaking the ragamuffin ringleader. The penny has come down with the wrong side uppermost, and theloud execration at